About OCD

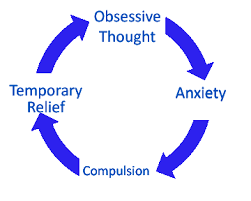

OCD develops when an individual has unwanted, intrusive thoughts (obsessions). The obsessions cause anxiety or distress, and the individual performs behaviors (compulsions) to lower that distress and "neutralize" the unwanted thoughts. Unfortunately, the relief from doing compulsions is only temporary, and the cycle of performing compulsions actually worsens (fuels) OCD over time. This cycle can be highly impairing and upsetting for the person who has OCD and family members who feel helpless to intervene.

OCD is caused by both genes and experiences. The tendency to get caught in the OCD cycle has a strong genetic piece, and it is common that a client being treated has close family members with OCD. Most people with OCD remember being aware of symptoms from childhood. The genetic component seems to involve getting stuck on thoughts and an overall sensitivity. However, the learned component of OCD involves the repetition of compulsions that relieve distress in the short term but make OCD much worse over the long term.

OCD is caused by both genes and experiences. The tendency to get caught in the OCD cycle has a strong genetic piece, and it is common that a client being treated has close family members with OCD. Most people with OCD remember being aware of symptoms from childhood. The genetic component seems to involve getting stuck on thoughts and an overall sensitivity. However, the learned component of OCD involves the repetition of compulsions that relieve distress in the short term but make OCD much worse over the long term.

Examples of Obsessions and Compulsions

Obsessions include thoughts and images of contamination, getting sick, harming oneself or others, having done or said something wrong, sinful, or offensive, and things not being just right.

Compulsions, or rituals, include repeated hand washing, asking others for reassurance, confessing, checking the internet for reassuring information, checking doors, windows, or appliances, counting, and rearranging or doing things until they feel just right.

* Mental Compulsions are often overlooked and can function in the same way as behavioral compulsions. For example, after an obsession, a person with OCD may count or say certain words in his or her mind.

Compulsions, or rituals, include repeated hand washing, asking others for reassurance, confessing, checking the internet for reassuring information, checking doors, windows, or appliances, counting, and rearranging or doing things until they feel just right.

* Mental Compulsions are often overlooked and can function in the same way as behavioral compulsions. For example, after an obsession, a person with OCD may count or say certain words in his or her mind.

Treatment for OCD

OCD requires a comprehensive treatment plan that involves the client, family members, and sometimes the school. The gold standard for treatment is cognitive behavioral therapy, comprised of the following steps:

1. Helping the client and family members to understand the nature of OCD, how obsessions and compulsions are fueled, and the steps of treatment.

2. Teaching the client to identify OCD thoughts and even to give a name to OCD.

3. Working with the client to recognize and respond appropriately to OCD thoughts, rather than taking those thoughts literally.

4. Helping the client to resist doing compulsions, even in the face of direct exposure to triggers for obsessions (known as exposure with response prevention). This step involves direct exposure to triggers for obsessions and skills to help the client avoid doing compulsions.

5. Providing strategies for the family to use in response to OCD, including helping family to disengage from rituals and managing disruptive behaviors that often accompany OCD.

Consultation with the family physician can help to determine if the client will benefit from medication, typically an SSRI such as Prozac or Zoloft. These medications do not eliminate OCD symptoms, but can be an important component of treatment for clients who have more severe symptoms.

The ultimate goal of treatment is to change the relationship that clients have with their thoughts. In other words, clients who can accept upsetting and unwanted thoughts and realize they do not need to respond to them are no longer at the mercy of OCD. When we stop treating OCD thoughts as facts and fighting anxiety by doing compulsions, OCD is deprived of fuel and eventually diminishes.

1. Helping the client and family members to understand the nature of OCD, how obsessions and compulsions are fueled, and the steps of treatment.

2. Teaching the client to identify OCD thoughts and even to give a name to OCD.

3. Working with the client to recognize and respond appropriately to OCD thoughts, rather than taking those thoughts literally.

4. Helping the client to resist doing compulsions, even in the face of direct exposure to triggers for obsessions (known as exposure with response prevention). This step involves direct exposure to triggers for obsessions and skills to help the client avoid doing compulsions.

5. Providing strategies for the family to use in response to OCD, including helping family to disengage from rituals and managing disruptive behaviors that often accompany OCD.

Consultation with the family physician can help to determine if the client will benefit from medication, typically an SSRI such as Prozac or Zoloft. These medications do not eliminate OCD symptoms, but can be an important component of treatment for clients who have more severe symptoms.

The ultimate goal of treatment is to change the relationship that clients have with their thoughts. In other words, clients who can accept upsetting and unwanted thoughts and realize they do not need to respond to them are no longer at the mercy of OCD. When we stop treating OCD thoughts as facts and fighting anxiety by doing compulsions, OCD is deprived of fuel and eventually diminishes.